Recovering from Addiction

- Pietro Gallino

- Oct 29, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2025

Sanctions and alternatives: the EU road to phasing out from Russian fossil fuels

On September 19th 2025 the European Commission proposed its 19th package of sanctions against Russia: for the first time, the measures included a ban on Russian LNG, starting from the end of 2026, a year before what was discussed a few months ago. The package, passed on October 23d, also extends the number of vessels subject to sanctions for being part of the so-called “shadow fleet”. From the official press release: “[the package] introduces a ban on imports of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) into the EU, starting January 2027 for long-term contracts, and within six months for short-term contracts, and tightens the existing transaction ban on two major Russian state-owned oil producers (Rosneft and Gazprom Neft). The EU is also listing a Tatarstani conglomerate active in the Russian oil sector. In parallel, the EU is taking measures against important third country operators enabling Russia’s revenue streams. This involves sanctioning Chinese entities - two refineries and an oil trader - that are significant buyers of Russian crude oil.”

This decision follows months of pressure from Washington, culminating in new sanctions on Lukoil and other Russian energy companies, to accelerate the European phaseout of Russian fossil fuels: exports of oil and gas are a key source of financing for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The EU Commission is now set on reducing imports to zero. Reaching this ambitious goal won’t be easy: in 2024, Russia supplied about 19% of European natural gas (down from 45% in 2022), via the Turkstream pipeline and LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) shipments. Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and France import Russian LNG. Gas piped via TurkStream goes to Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria.

This article will try to explain how Russia managed to spare some of its exports from previous rounds of sanctions and why it’s been particularly hard to cut off the imports. It will also analyse what the EU is doing to ensure supply security by establishing alternative procurement channels. Finally, it will explore some scenarios for future developments in this struggle for energy independence. Will the EU be able to gain strategic autonomy when it comes to fossil fuels and energy generation? What price – from an economic and strategic point of view – will have to be paid?

Reducing Dependence

Ever since Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, it has been manifest that the Union’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels is actively fostering the war.

In 2024 fossil fuels made up 65% of Russian exports, amounting to 250 billion dollars. Paradoxically, a significant share of these exports is directed to countries that sustain Ukraine and have imposed sanctions on Russia. As long as those countries buy Russian energy, they will be providing abundant liquidity to power Putin’s war machine.

But how dependent was, and still is, Europe on Russian energy exactly? Let’s look at the data. Before the full scale invasion, in 2021, EU countries imported 155 billion cubic metres (bcm) of Russian gas, which accounted for about 45% of total gas imports. Russia also supplied around 28% of oil imports with 108 million tonnes of crude and 91 million tonnes of petroleum products. Furthermore, Moscow is an important producer of uranium: in 2023, 23% of the uranium used in EU final nuclear products originated from Russia. It’s the equivalent of almost 3,5 tonnes. This was necessary to operate 18 nuclear plants around Eastern and Northern Europe.

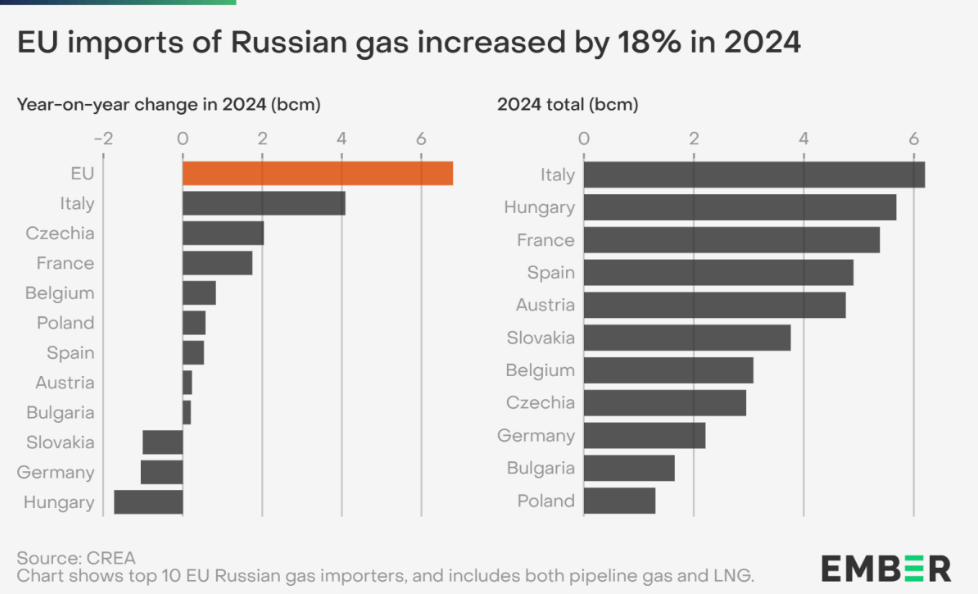

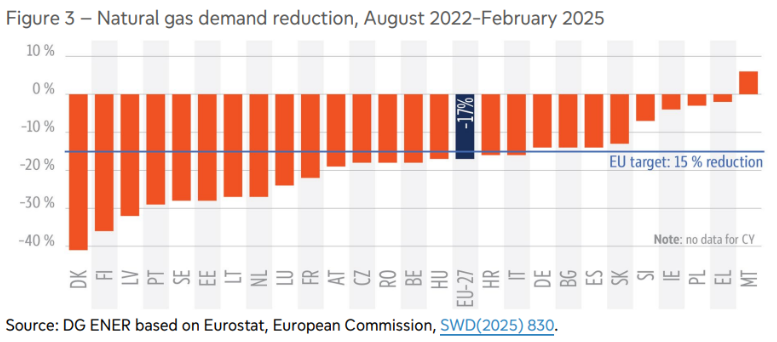

After the aggression, politicians around the EU quickly began thinking about ways to cut off energy imports from Russia. It wouldn’t be fair to say that they did not partially succeed. The EU launched its REPower EU plan in May 2022: renewable rollout and other factors such as energy savings contributed to an annual 60 billion cubic meters fall in natural gas demand. Despite this considerable reduction in demand, EU countries increased their Russian gas imports (LNG mainly) in 2024, as shown in the following graph

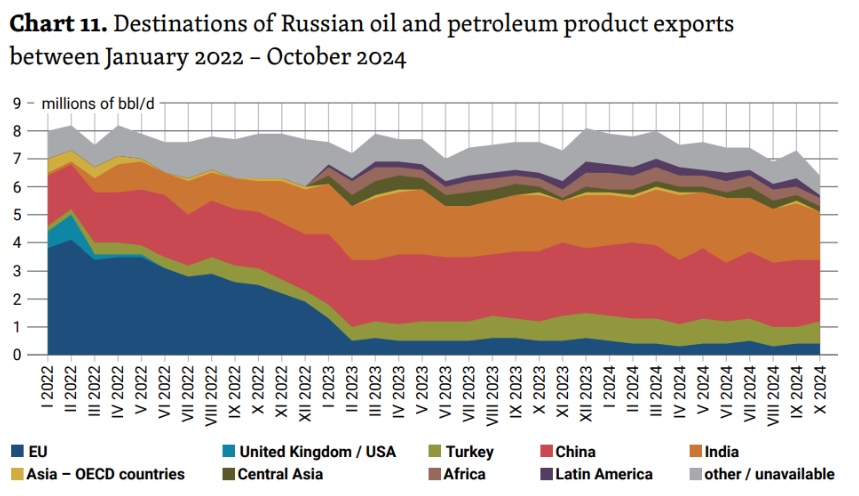

The EU has had far more success with oil: only 13 million tonnes of Russian crude entered the bloc in 2024. In 2022, Russian crude oil accounted for 27% of EU crude oil imports while now it only accounts for 3%. This is a direct consequence of the introduction and enforcement of EU sanctions, which banned Russian seaborne imports of crude oil from December 2022 and refined petroleum products from February 2023.

Still, two member states haven’t been able nor have they wanted to find other suppliers: Hungary and Slovakia. Russian oil represents over 80% of their total oil imports. These two countries are currently under Russian-aligned leaderships personified by Viktor Orbán and Robert Fico, who are going to fiercely oppose any package of sanctions against Russian energy. Regarding uranium, the Commission admits that severe supply security risks exist, and it supports a gradual approach based on tariffs rather than full out bans on imports.

In conclusion, even if the EU has managed to substantially reduce its dependency on Russian energy, it hasn’t been able to complete the task just yet, especially when it comes to natural gas. This has proven particularly hard to replace because of infrastructure and supply constraints (regasification plants, LNG availability) as well as Russian sanction-evading tactics, which will be explored in the next section.

Enforcing sanctions

Before explaining how Russia is avoiding EU measures, it’s good to do a quick recap of what energy related sanctions are in place.

The main and most effective sanctions imposed on Russia regard oil. The EU has prohibited the import of seaborne crude oil and refined petroleum products from Russia. In 2021, the EU imported €71 billion worth of oil: crude oil (€48 billion) and refined oil products (€23 billion) from Russia. Furthermore, price caps agreed with the G7 have been imposed. They prevent EU operators from providing transport or insurance services for the transport of Russian oil above the cap.

Three price caps are in place:

Russian seaborne crude oil, fixed at a maximum price of US$47.6 per barrel, following the 18th sanctions package

“Premium-to-crude” petroleum products, such as diesel, kerosene and gasoline, fixed at US$100 per barrel

“Discount-to-crude” petroleum products, such as fuel oil and naphtha, US$45 per barrel

The 18th sanctions package introduced an automatic and dynamic mechanism for future reviews of the Oil Price Cap: this system ensures that the cap is always 15% lower than the average market price for Urals crude in the previous period of six months

However, the EU hasn’t so far been able to strike Russian natural gas exports with equal strength. This weakness has to do with the difficulty in finding alternative suppliers, as well as political resistance across the bloc. Until its most recent proposal consisting of the 19th package presented on September 19th, and approved by the European Council on October 23rd, the Commission has abstained from imposing bans on gas imports.

The sanctions currently in place are mostly indirect:

A ban on the use of EU ports for the trans-shipment of Russian LNG

A ban on the import of Russian LNG into specific terminals which are not connected to the EU gas pipeline network

A ban on the provision of goods, technology and services for Russian LNG and crude oil projects

And this is why the new package is so “revolutionary”, as it consists of a direct ban on LNG imports from Russia. The newly-approved ban clashes with current market reality: the European Union imported €4.48 billion worth of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the first six months of the year, compared with €3.47 billion in the same period last year, according to Eurostat data. Still, however difficult it may prove, it is necessary for the EU to keep diversifying its natural gas imports.

Evading sanctions: a shadow fleet

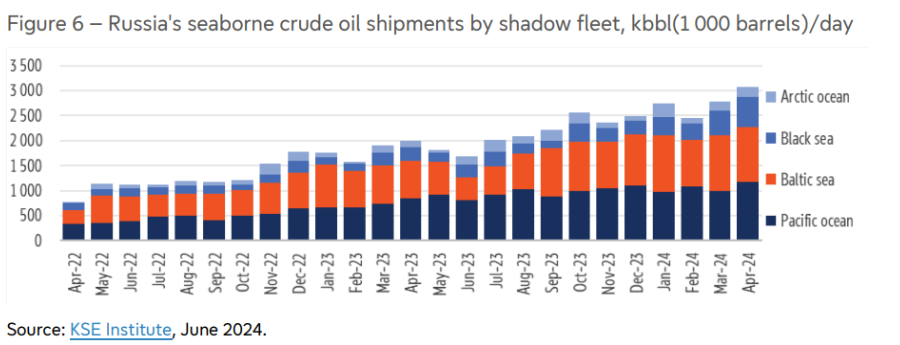

Imposing sanctions hasn’t been enough for them to work. Russia has found clever ways to evade them, from fake insurances to alternative transport networks. In the context of energy sanctions, the main threat to sanction effectiveness is posed by the so-called “shadow fleet”.

In short, the Russian “shadow fleet” consists of “a growing number of aging and poorly maintained vessels that make use of flags of convenience and intricate ownership and management structures while employing a variety of tactics to conceal the origins of its cargo”. These tactics include ship-to-ship transfers, automatic identification system blackouts, falsified positions, transmission of false data, and more.

The use of such a fleet is not new: sanctioned countries such as Iran, North Korea and Venezuela have adopted similar means in the past. After the oil sanctions imposed by the EU and the G7+ group, Russia took the concept of shadow fleet (which already existed) to a new level in scope, sophistication and numbers. In its effort to build up the fleet, the Russian government has focused on:

Shifting tankers previously owned by Russian entities to new management companies.

Buying vessels over 15 years old from the cleared fleet.

Acquiring very old vessels (20+ years) from both shadow and cleared fleets.

In the words of Nick Childs from the International Institute for Strategic Studies: “It has been estimated that more than 80% of Russia’s shadow fleet of tankers has been purchased on the used market since the spring of 2022 at a cost of some $10 billion, with as many as 650 vessels believed to have been involved in shadow-fleet activities [...] Recently, close to 70% of Russian seaborne oil and product exports are thought to have been carried in shadow tankers, and 89% of crude-oil exports.”

It is obviously very complicated to estimate the volume of oil circulating on this fleet. Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) estimates for June 2024 put the exports at 4.1 million barrels a day. Windward experts estimate that since 2022, the shadow fleet has transported over 142 million barrels of Russian crude and oil products. KSE experts estimate that, from January to September 2024, Russia's shadow fleet allowed it to realise an extra $10 per barrel for its oil sales, generating $8 billion in surplus earnings (compared to a no-fleet scenario).

China, India and Turkey are the main importers of oil and oil products transported by the shadow fleet, and Russian oil products in general. However, the situation is evolving: following US sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil, China state-owned oil majors decided to suspend imports of Russian seaborne oil. Pipeline imports, for now, continue.

So what can the EU do to counter the shadow fleet? The bloc’s countries haven’t been idle, and they have agreed on various measures:

Banning the entry of vessels into EU ports if they are involved in suspect ship-to-ship transfers.

Monitoring closely the sale of tankers to third countries to prevent their use for transporting oil above the price cap.

Introducing listings of vessels under sanctions in the context of Russia's war on Ukraine.

Engaging in dialogue with the flag States. EU delegations have been instructed to reach out to the countries hosting and providing services to the shadow fleet.

However, these efforts have proved insufficient. That is why EU authorities and some Member States (like Denmark) have decided to bring pressure on the shadow fleet to the next level in terms of inspections and patrolling. In the words of president Macron, Europeans “have now decided to take a step forward by implementing a policy of obstruction against suspicious ships in our waters.” On October 2, 2025, French navy soldiers boarded a suspicious tanker, the Bocaray, arresting two people for “not cooperating” and not justifying the tanker’s nationality. The tanker, apart from being considered a member of the shadow fleet, was suspected of having a role in the Copenhagen airport drone incident of September 22. This initiative signals a newly found proactiveness against Russian manoeuvres, in defence of European interests.

Towards Diversification

With its decision to aggressively decouple itself from Russian energy, the EU has provoked a major shift in regional and global energy markets, as the bloc’s demand will have to be satisfied by someone else.

Beginning from natural gas, since the launch of the REPower EU plan, significant progress has been made in renewable energy deployment and energy efficiency across the Union, prompting a reduction in demand.

Aside from this reduction, reliable alternative suppliers rose to the occasion: Norway, for example, consolidated its position as the top supplier of non-liquified natural gas with a share of 50.8% of imports in the second quarter of 2025 (compared with a 43.6% share for the same period in 2024).

New import routes are also being exploited. It’s the case of the Southern Gas Corridor, a 3500 km pipeline that supplies gas to south-east European countries from the Shah Deniz gas field in the Caspian Sea, off the coast of Azerbaijan. It entered into operation in December 2020, and it delivered 11.7 billion cubic meters of gas to the EU in 2024, a 44% increase since 2021.

EU Member States (mainly Italy) are working with countries from North Africa (Algeria and Libya) and the Middle East to create a Mediterranean gas hub. Italian hydrocarbon titan ENI signed a $8billion agreement with Libya’s National Oil Corporation, “aimed at increasing gas production to supply the Libyan domestic market as well as to ensure exports to Europe.” Over the next three to five years, both Algeria and Libya could potentially make available 10 to 15 bcm of incremental annual volumes for exports through the TransMed and Greenstream cross-border gas pipelines to Italy.

The Union is also working to develop internal supply. Romania, in particular, is set to become the EU’s largest exporter of natural gas with the Neptun Deep field, expected to start production in 2027. It holds an estimated 100 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas, and it will be one of the EU’s most significant natural gas reserves.

Finally, EU authorities are working to ensure LNG infrastructure (regasification facilities and interconnectors) are fully capable of managing increased flows efficiently. The global LNG market is expanding rapidly (it grew by 2.4% in 2024 to 411.24 million tonnes). At the end of March 2022, the EU and the US adopted a common declaration on increasing LNG trade. A majority share of EU LNG imports is now provided by the US.

When it comes to oil, after the ban on imports from Russia, EU countries quickly managed to find alternative suppliers to satisfy their needs. As seen before, Russia’s share of EU imports fell considerably thanks to sanctions, diplomatic efforts and infrastructural development. The decrease of crude oil import from Russia was compensated by increased imports from the United States, Norway and Kazakhstan.

At the end of 2024, Czech operator MERO completed an upgrade of TAL, which carries oil from tankers in the Italian port of Trieste to Germany where it feeds into the IKL pipeline to the Czech Republic. Starting from March 2025, The Czech Republic began increasing imports of crude via the expanded TAL pipeline, replacing imports of Russian oil through the Druzhba pipeline. The expansion gives the country full independence from Russian supplies. On the diplomatic side, the Commission received a mandate from the Council of the EU to deepen geostrategic relationships with the Gulf countries, a move with obvious energy related repercussions.

Pressure from the US

The EU has been relatively successful in replacing Russian fossil fuels. Nevertheless, efforts to diversify procurement are being undermined by Donald Trump’s mercurial approach to foreign relations. Trump’s aggressive negotiation tactics pose serious risks to the bloc’s interest. The US President is especially keen on boosting domestic production of natural gas and oil (even if this hits producer companies that have to face low prices and full storages), and he has repeatedly urged EU countries to buy more American energy (which, as shown, the EU has already been doing).

These requests culminated in the infamous “tariff deal” of July 27. Even if the details of this agreement aren't clear at all, it looks like Commission president Von der Leyen pledged to buy $250 billion of US oil and gas a year until the end of Trump’s term. There are many caveats: first and foremost, the European Commission has no power to coerce companies into buying this energy. Secondly, experts agree that these numbers don’t really make sense: the EU spent €375 billion on energy imports last year, including €76 billion from the US, meaning the bloc would have to essentially triple its American imports over the next three years. This would imply ignoring other providers, such as Norway, that provide cheaper gas via pipeline, considering that gas from the US would have to be liquefied.

These sky-high figures could just be a way to please Trump without actual consequences; still, it’s clear that surrendering such a significant portion of the EU’s energy supply to an increasingly unreliable partner such as the US would be a risky move, one that could expose the bloc to economic and political coercion over the following years. EU diplomats will have to navigate Trump’s unpredictability to ensure both support against Moscow and energy independence. The Union must pray its promise won’t be tested

Pockets of Resistance

Before concluding, it’s important to cover two major hurdles towards EU autonomy (not limited to energy) from Russia: Hungary and Slovakia. For years now, both countries have exploited unanimity rules in the EU to block major measures against Russia. With the sixth sanctions package, adopted in June 2022, the EU granted Hungary, Slovakia and Czechia an exemption from the Russian crude oil ban. This exemption allowed these landlocked countries to continue receiving Russian crude via the southern Druzhba pipeline The purpose of this exception was to give them extra time to reduce reliance on Russia. The Czech Republic proved up to the challenge; the other two countries did not, mainly because of a lack of political will to act in this sense.

Instead they kept importing oil at rates higher than pre-invasion levels. Both Viktor Orbán and Robert Fico have threatened to block military and financial aid to Ukraine, should this exception be terminated. At the same time, these leaders have adopted a fatalistic rhetoric, quoting geography and the absence of alternatives as the main reasons behind their choice. Experts are sceptical of their statements. In the words of Isaac Levi, leading analyst at CREA:” Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, prices at the pump for consumers have not gone down, meaning that it's basically Orbán’s government and the company MOL who are profiting from the high reliance on Russian crude even though they don't need this oil and other countries have been able to successfully diversify. Hungary is being very persistent in not reducing its reliance on Russian crude oil, even though they have the capacity and alternatives to buy non-Russian crude oil through the Adria pipeline, which could provide enough capacity for the total demand of Hungary and Slovakia.” In 2024, Hungary and Slovakia were 87% dependent on Russian crude transported through a single pipeline, which transits a war zone and experienced two significant outages in 12 months. Pressure on these countries is mounting, even from traditional allies such as the Trump administration: Orban has ignored a direct call from the US president to stop buying Russian oil. We’ll see how he and Fico will react as Washington’s calls to end imports grow stronger.

Conclusion

The task the EU took on in 2022 was nothing short of monumental: even if important criticalities remain, the progress that has been made is relevant. It shows that when the bloc’s countries unite behind a common goal they can achieve significant progress in a relatively short timespan. The REPower EU platform and other common projects could be relevant foundations towards future advancements in energy independence and further market integration.

Approving the package is a relevant milestone in shaping the future of the EU energy landscape. If the bloc can avoid becoming too reliant on the US for its fossil fuels needs, and at the same time convince Hungary and Slovakia to drop Russia, the Commission will have succeeded in a critical mission for the Union’s future.

Bibliography:

Payne, Bayer, Irish: After Trump pressure, EU aims to bring forward Russian LNG import ban, Reuters, September 19, 2025

Payne: EU looks to accelerate ban on Russian LNG in new sanctions package, official says, Reuters, September 18, 2025

Workman: Russia’s Top 10 Exports, World’s top exports 2024

Kardas: Conscious uncoupling: Europeans’ Russian gas challenge in 2023, CEFR, February 13, 2023

European Commission: REPower EU plan

Hancock, Tani: German demand soars for Russian LNG via European ports, Financial Times, January 28, 2025

European Commission: Phasing out Russian fossil fuel imports, July 9, 2025

European Commission: Roadmap towards ending Russian energy imports, June 5, 2025

European Commission: Sanctions on energy

European Commission: EU adopts 18th package of sanctions against Russia, July 18, 2025

Aizhu, Tan, Liu: China state oil majors suspend Russian oil buys due to sanctions, sources say, Reuters, October 23d, 2025

Caprile, Leclerc: Russia's 'shadow fleet': Bringing the threat to light, European Parliament, November 2024

Childs: Russia’s ‘Shadow Fleet’ and Sanctions Evasion: What Is To Be Done?, IISS, January 2025

European Commission: Diversification of gas supply sources and routes

European Commission: The EU and the U.S. are strategic partners who work together to enhance energy security as well as the full phase out of Russian fossil fuels.

Reuters: Czechs to start oil imports through upgraded TAL pipeline in April, Reuters, March 27, 2025

European Commission: Commission welcomes the adoption of the EU mandate by the Council to launch negotiations with the six GCC countries, July 18, 2025

Jack: The EU’s ‘fantasy’ $750B energy promise to Trump, Politico, July 29, 2025

Levi et al.: The Last Mile: Phasing Out Russian Oil and Gas in Central Europe, CREA, May 15, 2025

The Insider: Hungary and Slovakia could diversify away from Russian oil if they wanted to, experts explain, The Insider, October 3, 2025

Comments