Losing the North Star

- Daniel Trangeled

- Sep 19

- 20 min read

The current state of the Democratic Party, and how they can recover in 2028

On November 5th 2024, US citizens across the 50 states returned once again to the polling stations for an election which saw a party thrown into chaos. The Democrats, fighting to maintain their control of the White House, faced not only Kamala Harris’ loss to former president Donald Trump, but the loss of their Senate majority, leaving the party with virtually no influence across all branches of government. Now, 9 months into the second Trump administration, the opposition still struggles, with unprecedented foundational disagreements across the board. From local councillors to the very top of the party, regarding anything from communication strategy to the most basic aspects of party policy, the very future of the Democrats as a cohesive unit is being questioned, not to mention their electability in the coming elections. Donald Trump and his second administration have shown no signs of slowing momentum, and though his successor, whoever they may be, is still years away from running to take his place, continued Republican popularity remains a massive threat to the Democrats. What the opposition does in these early stages, and how they approach their upcoming campaigns, will prove pivotal to not only the future of the party, but the country as a whole.

What caused the losses in November?

As Donald Trump has settled into the Oval Office, and keystone Republican policy has already been passed through both legislation and executive orders, many have begun to reflect on what allowed the controversial president to return to the White House. After all, President Biden inherited a nation ravaged by COVID-19 and a broken supply chain, yet returned surprisingly strong results for the economy. GDP grew, unemployment went down, and the recession most people anticipated was less disastrous than the data predicted: what economists call a “soft landing” given the circumstances. Major legislation included the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, which both sought to bring stability back to the recovering US economy.

President Trump, despite Biden’s successes in office, managed to successfully persuade the country to grant him another term as president. The reason behind this victory may lie not within the facts, rather in the perceived reality of many Americans beyond the concrete effects of Biden’s policies. Democratic campaign consultant James Carville, when discussing strategies for the 1992 Clinton campaign, had famously said “it’s the economy, stupid”, referring to the fact that the economy’s performance and the stability of personal finances is the single most important factor in any election. The fact remains that, despite the on-paper strong economic recovery, the people were still experiencing high prices without the wages to match them, whereas much of the Biden administration’s campaigning revolved around foreign policy and climate change. The policies of so-called “Bidenomics” were simply not sufficiently communicated to the public, both throughout the president’s tenure as well as during the campaign. Though economic policy was certainly a priority, it typically focused on building long-term stability and growth, goals which simply did not relieve current financial pressures faced by voters. The lack of a clearly communicated economic plan, as well as a less than straightforward immigration agenda, gave the Republicans free reign to criticise the administration’s inaction. Trump took advantage of the new media, going on a podcast tour across internet and radio shows especially popular with young men, mobilizing a voter base disgruntled with the Democrats’ focus on social policy. Historically, incumbency leads to an electoral advantage, with it being easier to raise money for and campaign a known face as opposed to having to build a candidate’s image from scratch. It seemed, however, that the relatively passive and unclear Democratic campaign paved the way for Trump’s criticisms of the administration to resonate far more with ordinary people, no matter what Biden and Harris had managed to accomplish in their term.

President Biden himself also shares much of the blame for the loss of the White House, both throughout his governance as well as in his short-lived attempt at re-election. During his 2020 campaign, much of Biden’s rhetoric indicated that he would serve as a transitional president, in an effort to reverse the impacts of the first Trump presidency, focusing specifically on wanting to repair the US’s relationship with its allies abroad and in better tackling the pandemic. Given Biden’s age, many interpreted his statements as him planning to govern as a one-term president, allowing the party to push ambitious legislation without burdening the president’s actions with the consideration of their effects on a re-election campaign. The president was further bolstered by a surprisingly successful 2022 midterm result, at a time where polling predicted decisive Republican victories nationwide. These midterms reinforced an important aspect of Joe Biden’s success as a politician, namely his history as an underdog performer and someone who persisted amidst doubt from all sides to consistently bring successful results. The decision to run for a second term was thus accepted by the establishment throughout his tenure and in the early stages of the campaign, making his exit in late July a disaster. Harris was given less than 100 days to present herself as a viable candidate, without the exposure and preparation she would have been privy to had Biden committed to serving one term. Though she managed to raise an impressive amount of donations given the late start, was supported in her pick of Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her vice president, and eventually united the party around her candidacy; the cards were simply stacked against the vice president.

There was not one root cause for the November losses, rather a combination of different actions - and more importantly inactions - which led to a Republican sweep across the board. The Democrats have simply been struggling to come back ever since.

A Headless Party

The current state of the Democratic party is arguably weaker than ever before in modern US politics. Having lost control of both the executive and legislative branches in November, and no clear candidate for the 2028 Presidential elections, the party currently lacks strong leadership. Senate and House Minority Leaders Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries respectively, though officially being at the helm of the party, have failed to establish a strong Democratic presence in either of the chambers of government, or to foster a sense of unity between its voters. Massively diverging ideologies between the progressive and moderate wings of the party have made any joint values difficult to communicate to the public. This confusion throughout the party’s representatives in Washington has made any recovery from the November losses at best slow, and at worst directly harmful to any prospects of a comeback.

These divisions have extended to perhaps the one thing Democrats could previously get behind: a basic opposition to the Trump administration. Though the party is united in the principles of resisting President Trump’s policies, there is a persistent divide on how the approach to doing so should look. Some, such as the aforementioned James Carville, believe that the best move for the party is to “roll over and play dead”, arguing that waiting for the Republicans to dig their own grave with controversial policies will eventually win voters back and restore trust in the Democrats. This is similar to the 2020 campaign strategy, where Trump’s controversial rhetoric and poor handling of the pandemic made Biden, who had united his primary contenders behind him, seem better equipped to lead the nation. Others, however, have argued that a tactical retreat would only make the party seem weaker in communicating a clear alternative to the Trump administration. Critics have argued that Carville’s approach is effectively what the party has been doing since the election, and that it is the lack of consistent, unified opposition which continues to prolong a Democratic recovery. They further reflect on some of the most influential modern voices of the party, such as Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, and how their success came from ambitious visions despite their own partisan challenges and political situations.

The leadership in Washington has thus far been hesitant to comment on plans for the future of the party. Though the country has seen moments of impassioned resistance to the Republicans in Congress, such as Cory Booker’s record-breaking marathon speech protesting the actions of the Department of Government Efficiency, it has not been enough. Polling has shown that voters have thus far been unimpressed with the party since Trump took office. Party registrations have been on a consistent decline since the election, with criticism being especially directed against Schumer and Jeffries for their inability to effectively articulate Democratic values and their unwillingness to stand up to Trump.

Ideological Uncertainty

The Democratic party, just like the Republicans, has always had various factions throughout its ranks. This is only natural given the rigidity of the two party system in American politics, and the vastly diverse demographics any party must encompass to be able to win elections. However, the Republican victory last November has led to these factions becoming further split as disagreements have grown. What used to be different groupings under a united banner has evolved into entirely different visions on how the party should operate, both in the short-term in its opposition to Trump as well as what the party’s values actually are.

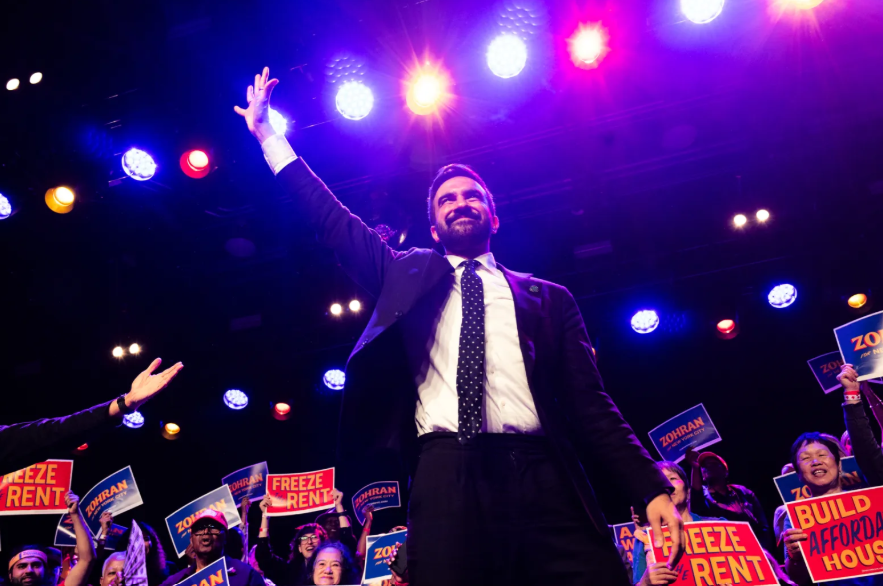

The progressives of the party, though by no means being a new wing of the Democrats, have further become a challenge to the party establishment. This has particularly been through a staunch opposition to the continued funding of Israel despite the conflict in Gaza, an issue which has remained controversial throughout the party and country. The progressives’ most recent figure is New York City Councillor and mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani. Mamdani, who won a decisive victory in the June primaries against former Governor Andrew Cuomo, has become nationally and internationally known for his social media campaigning and interactions with everyday New Yorkers. The New York race garnered attention throughout the country, not least because of what the primaries represented. Mamdani is a registered member of the Democratic-Socialists, and was financed not by large corporations or Super-PACs, rather entirely off of individual donations. This was in stark contrast to Governor Cuomo, who not only outfunded his opponent through mostly corporate donations, but was also backed by the majority of the establishment as a more moderate candidate to replace Eric Adams. Many have also used Mamdani’s victory in the primaries as evidence for the need to run more progressive candidates throughout the country, arguing that unapologetically campaigning on more left-leaning policies would be more successful than trying to win back the centre at the cost of Democratic values. However, the extent to which the tactics displayed in New York could be applied to the country as a whole is questionable. Mamdani’s campaign was heavily reinforced by his personal charisma and understanding of social media, qualities which cannot necessarily be learned or applied by any traditional politician. New York City is also an area considerably more progressive than other parts of the country, and though Mamdani’s win remains impressive, a Democratic-Socialist would arguably be far less likely to win in anywhere else.

A newer wing of the Democratic party is also on the rise, however, namely the so-called “Abundance” faction. Introduced by researchers at the Niskanen Institute, and brought to the mainstream through a book published by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson of the same name, the abundance faction diagnoses the systemic issues in modern America as stemming from the over-regulation of government projects, slowing economic development despite positive intentions. The faction is reminiscent of Bill Clinton’s “Third Way” ideas in its neoliberal characteristics, arguing for greater cooperation with the private sector, an expansion of welfare programmes, as well as a massive investment into green power in an effort to become energy independent. Supporters of the abundance movement argue that it is only through a more realistic approach to liberal governance that Democrats can effectively enact real economic development and social progress. Its opponents, however, have criticised it for being far too corporatist in its approach, specifically in its ignorance of the role a lack of government oversight of private sector activities has played in many of the country’s systemic problems. Nevertheless, the abundance faction represents a new threat to the establishment, and though they are certainly a newer wing of Democrats, they will undoubtedly play a deciding role in the politics of the party going forward.

The main challenge the party faces in deciding which faction to lean into stems from the uniqueness of the current US political landscape. Other than Joe Biden, whose campaign heavily benefited from the instability caused by the COVID pandemic, no candidate has truly beaten Donald Trump in a head-to-head race. Though the president will not be in contention in 2028, there is still no playbook for the Democrats in tackling the MAGA movement at the national level, with the electorate, and country as a whole, having changed dramatically even since 2020. There may not be one correct ideology for the Democrats to promote at a national level, with the best approach likely varying from state to state. However, if the party wishes to make a comeback in the next elections, certain foundational policies will have to be agreed on between its factions, otherwise risking splitting the vote and granting the Republicans further opportunities to capitalise on internal disagreements.

The Invisible Primaries

Though the next presidential election is still years ahead, speculation as to who can challenge the Republicans in 2028 has already begun. US presidential campaigns tend to start long before the election, especially for the parties contending the White House during a given election. This is partly due to the sheer amount of fundraising involved in the US compared to other democracies, as well as the vast media attention candidates receive from involving themselves in the race. We are now experiencing the phenomenon which has been dubbed by analysts as the “Invisible Primary” stage of Democratic politics, in which potential candidates for the 2028 ticket are beginning to present themselves to the nation as viable faces for the party’s nomination.

Although there is no defined playbook for choosing presidential candidates, there are certain expectations for potential nominees. There are, of course, basic requirements, such as an ability to effectively fundraise and, in theory, appeal to as broad a proportion of the populace as possible. However, there are certain historical patterns specifically for the Democrats in terms of which politicians they typically rally behind. As opposed to the Republicans, who have often run businessmen and other “outsiders” to the political world, Democrats have tended to stick to elected officials. In fact, though many Democratic candidates have had private sector experience, career politicians and lawmakers have been far more common nominees for the party, especially when compared to their opponents. A significant factor in US presidential elections, given the importance of certain states in swinging the electoral college, is also the origin of the candidate. However, this has in recent times been less important than one might think; Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris have all come from deep blue states. Strategic geographical choices for the Democrats have actually tended to be larger factors in selecting the vice presidential nominee, often picking running mates from more conservative states to target moderate Democrats or left-leaning Republicans. Perhaps the most famous example of this was John F. Kennedy’s choice of Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, but Tim Walz’ more recent campaign could also be interpreted as an attempt to appeal to the Upper Midwest of the country.

Blue candidates have historically been expected to represent high moral standards, with campaign messaging typically focusing on the government’s responsibility to provide for its citizens and a personal sense of duty in upholding democratic values. However, some have begun to question whether the current political climate requires politicians to “play dirtier” in their campaigns, or whether doing so is an abandonment of the traditions the party is built on. The Democrats will likely have to incorporate a mixture of what has worked in the past and an effective counter to the modern-day Republican party, both in regard to who they nominate and in how they campaign.

The “Known Knowns”

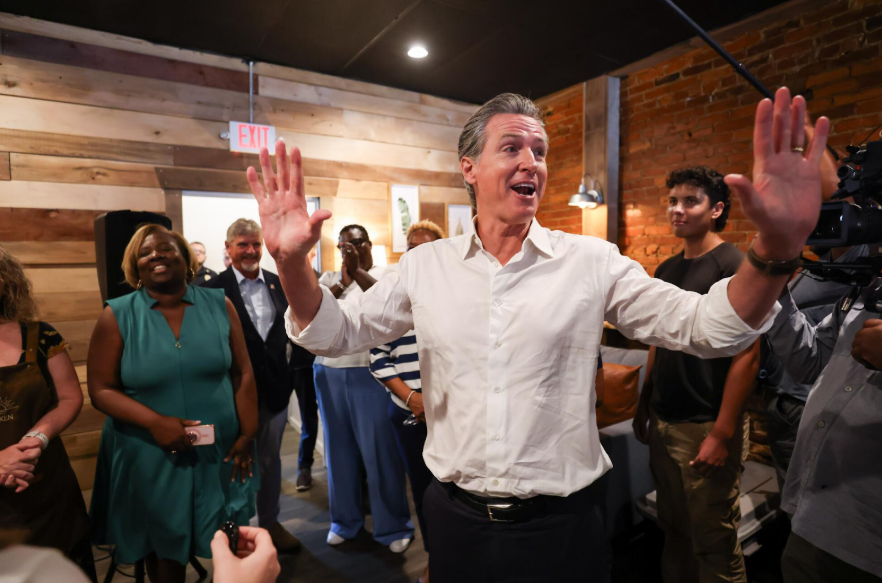

The US media has already begun to hone in on some of the more obvious candidates for the nomination, especially those who already have the exposure and name recognition to be considered. Perhaps the clearest candidate out of any active Democratic politician is Gavin Newsom, the Governor of California whose tenure is set to end in 2026 without the opportunity for re-election. Newsom has been on the national scene for years, and has more recently began expanding on this popularity, taking part in official visits to other states and being one of the harshest critics of the Trump administration. This was further amplified when President Trump controversially deployed the National Guard to the city of Los Angeles in July, which the governor responded to with lawsuits and outrage at what he deemed as a violation of the constitution. More recently, Newsom has also been leading the resistance to Trump’s redistricting initiatives in Texas, opting to fight fire with fire and launch a similar proposal in California. The governor has shown himself to be a fiercely competitive politician who aptly plays the political game, having debated other governors on television and not being unwilling to employ fiercer tactics against opponents. A moderate-leaning Democrat, he has also begun to mirror Republican campaign strategies to try to win back the centre of US politics, having started his own podcast to engage with both Republican and fellow Democratic politicians, and more recently having begun to be far more active on social media. Newsom, despite seeming to be gunning for the nomination, would by no means be an uncontroversial candidate. The governor has already had to endure a recall election in 2021, and has been criticised for his handling of poverty and safety in his home state. Nominating a Californian for a second time could also prove to be a risk, especially as the Democrats already struggle with the perception as a party out of touch with rural America.

Pete Buttigieg has also been a consistently supported candidate for the nomination. A US Army veteran and former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, Buttigieg ran for the presidency himself in 2020, later serving in the Biden cabinet as the Secretary of Transportation. “Mayor Pete” has been known for his unapologetic upholding of his principles, and for being one of the best communicators of Democratic values and policies, especially in his consistent efforts to engage the Republicans directly in conservative media and territory. Buttigieg caught the attention of the media when, despite expressing willingness to remain active in US politics, he opted not to run for an open Senate seat in Michigan in March. Given the very high likelihood of victory, many in the party have interpreted the move as paving the way for a second run at the presidency in 2028. However, the former secretary would have one particularly major challenge to his success, namely his role in the previous government. The Biden administration and its legacy remains deeply unpopular in many parts of the country, and though his role in overseeing transport would have been comparatively unimportant, it would undoubtedly be a factor in a presidential race. Rumours surrounding President Biden’s physical ability to execute the oath of office have also severely weakened the image of any of his former cabinet members, especially in regard to the extent to which these health issues were subject to an orchestrated and coordinated cover-up by the rest of the administration. This is also why, though many speculate about Kamala Harris seeking the nomination once again, she would be unlikely to garner support from either the party or the country, despite her clean record and experience. In fact, despite Harris personally denying the notion, it is far more likely that she enters the 2026 California gubernatorial race to replace Newsom, given that she still enjoys broad support in her home state.

Untapped Potential

There are also candidates who, despite having dipped into the limelight, have not experienced substantial media exposure across the nation. One of these cases is Governor Wes Moore of Maryland, who despite fervently denying any ambitions to launch a 2028 campaign has been a frequently brought up name as a future nominee. Moore holds an extremely diverse background, having served in the US Army and having vast experience in the private sector prior to entering politics. The governor gained national attention after the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in 2024, in which he took a personal involvement in raising awareness of the crisis to the White House and the nation. Governor JB Pritzker of Illinois has been another potential contender, having recently announced his campaign for a third term in the state. A self-made billionaire known for his blunt communication style, Pritzker is seen by many as being the Democrats’ closest reminder of Trump, despite having fiercely attacked the president and being one of the leading figures in resisting him. A Pritzker nomination would not be uncontroversial, however, and would bring the party back to the question of whether the best way to counter the Republicans is to have a “Trump” of their own, or if this would simply continue to alienate progressives. Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania would also be an interesting choice for the party. After all, Shapiro, a veteran of Pennsylvanian politics at all levels, is someone many thought would be Harris’ pick for vice president. Given his continued popularity in a state as pivotal as Pennsylvania, the governor benefits from the perception that he could have swung the state blue, and appealed more broadly to the moderate democrats in the swing states.

However, there is also another perspective about who the Democratic nominee will be, namely that the party requires a completely fresh face. Many of the Democrats’ most high-profile politicians came into their races as the underdogs, not being especially well-known across the national scene and only making waves in the run-up to the caucuses. Former president Barack Obama, for example, was a relatively unknown senator before his landmark speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. Bill Clinton, spearheading the Third Way faction of the party, trailed far behind his competition in the early stages of the primaries, having to fight to shed his image as a regional candidate to win the nomination. Obama and Clinton each faced similarly “confused” Democratic parties. Clinton’s victory came after three consistently popular Republican administrations, including the biggest loss in American presidential history after winning only one state in the 1984 elections. Obama, like Clinton, represented a much-needed freshness in the Democratic party, serving as a remedy to the unsuccessful 2004 elections. Picking candidates from the wilderness of the party has strong historical precedent, and perhaps a less exposed candidate with new energy would bring it back to its former levels of outreach. This is reinforced by the youthfulness of many more recently elected officials, either at the state level or in Washington, such as Senator Jon Ossoff in Georgia or Texas State Representative James Talarico. The younger sides of the Democratic party have stuck out in the digital space, having shown their proficiency in communicating through new media to counter the Republicans’ long-time domination online. Seemingly simple characteristics, such as being able to effectively engage voters in the digital space, or having an understanding of challenges facing smaller constituencies, may be what the Democrats need to look for when considering candidates in 2028, even if untested on the national scene.

Opportunities in the Midterms

The 2026 midterm elections will undoubtedly be a strong indicator of the progress of the party, and will prove to be the first real test the Democrats have to face in reclaiming influence in US politics.

President Trump, through his direct personal involvement with the legislative aspects of his administration, has given the Democrats the opportunity to capitalise on the unpopularity of Republican policy so far. However, this would require immense coordination in campaign strategy across the country if the Democrats wish to re-create the 2018 “Blue Wave” which took place halfway through Trump’s first administration. A crucial aspect of this effort is already being pursued by the DCCC, namely a return to the “50 State Strategy”. The policy, introduced by then-DNC chair Howard Dean in 2005, involves establishing a greater presence in virtually every major ongoing election nationwide, especially in Republican-controlled parts of the country. The tactic has been credited with granting the Democrats their legislative majorities in 2006 and 2008, and the establishment is hoping to use this to reclaim their image as a party of the people. DNC Chair Ken Martin has already pledged to dedicate a baseline of 17,500 USD to each state party, representing a 12% increase in donations from Washington at the local level. (Solender, 2025).

The Trump administration has thus far proven to be unique in many ways, especially in his rapid consolidation of power within the executive branch in moves that reminisce the ideology behind the unitary executive theory. Though the president’s actions have been described as an attempt to garner a tighter grip in maintaining control of government, this may also have the effect of centring the midterms more around Trump’s actions than on those of individual representatives in the House and Senate. The One Big Beautiful Bill, Trump’s tax and spending bill which very closely passed both houses on July 3rd, has not experienced broad popularity among the base of the party, especially in regard to the tax cuts for the wealthy and rollback of health guarantees. The White House’s rhetoric in its success in “ending wars” has not proved particularly impactful to many in the country, again going back to the idea of domestic issues, and more specifically the economy, being the primary motivator of Trump's re-election. The president has also experienced increasingly serious damages to his personal brand, through his various deployments of the National Guard being protested as unconstitutional, and more recently the controversies surrounding his relationship with disgraced financier and child sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein.

A strategy based entirely around an opposition to Trump is not a sustainable solution, however. Midterm elections are in many ways far more nuanced than presidential elections, in that voters prioritise local and state issues to a significantly higher degree. Recent election results have even indicated that the midterms are often unshackled from presidential popularity, as was shown with the Democratic successes in 2022 despite Biden’s poor approval ratings. After all, unlike most western democracies, neither the Republicans or Democrats have singular party leaders for their members and representatives to gather behind. Many midterm voters opt to vote based on their party preferences or personal loyalties to their local representatives, rather than which party controls the White House. If Democrats only campaign based on the actions of Donald Trump, they could face an uphill battle in being able to effectively resonate with voters, especially if their attacks come at the cost of promoting policies of their own. Leaning into the ways in which Republican policies have harmed the nation, especially relating to economic stability, is a far more effective strategy. Midterm elections are just as much a test of the administration’s legislative agenda as they are a popularity contest. Honing in on the impacts national policy has had at the state level is an opportunity to again appeal to ordinary people. If successful, it could open up for voters to criticise the administration through the lens of local impacts as opposed to a personal dislike of the president.

The future of the Democrats depends on many decisions, regarding virtually every aspect of party politics. In a country as diverse and complicated as the US, very few of these decisions will be objectively right or wrong, and no one strategy can truly apply to every part of the country. As 2026 slowly approaches, the Democrats have the chance to gauge the effects of these decisions in real time during the midterms, and evaluate how the voters respond to different approaches taken in the campaigns. If the Democrats hope to win back Washington in 2028, 2026 is their moment to prepare for that comeback.

Bibliography:

Anuta, J. et al. 2025 Mamdani’s social media savvy comes at a cost POLITICO, July 20 2025

Barabak, M. 2021 Kamala Harris, the incredible disappearing vice president BBC, November 10 2021

Carville, J. 2025 It’s Time for a Daring Political Maneuver, Democrats The New York Times, February 25 2025

Cohen, D. 2025 Biden the ‘only’ Dem who can beat Trump, Chris Coons says, POLITICO, June 30 2024

Mosley, T. 2024 How Biden's campaign strategy has changed from four years ago NPR, March 6 2024

Pastis, S. 2024 Here Are The Biggest Moments From Trump’s ‘Bro’ Podcast Tour Forbes, October 29 2024

Fandos, N. et al. 2025 How Zohran Mamdani Stunned New York and Won the Primary for Mayor The New York Times, July 1 2025

Ifill, G. 1992 THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: Strategy; Discipline, Message and Good Luck: How Clinton's Campaign Came Back The New York Times, 5 September 1992

Kiley, J, et al. 2025 Trump’s Tariffs and ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Face More Opposition Than Support as His Job Rating Slips Pew Research Centre, August 14, 2025

Klein, E. 2025 How Groupthink Protected Biden and Re-elected Trump The New York Times, May 21 2025

Lapham, J. 2025 Kamala Harris rules out running for California governor BBC, July 30 2025

O’Connor, B. 2002 Policies, Principles, and Polls: Bill Clinton’s Third Way Welfare Politics 1992–1996 Australian Journal of Politics and History, December 18 2002

Saldin, R. et al. 2025 The rise of the abundance faction Niskanen Center, June 4 2024

Solender, A. 2025 DNC unveils new 50-state strategy: "Organize everywhere" Axios, April 24 2025

State of Maryland. 2025 2025 State of the State Address State of Maryland, February 5 2025

The New York Times. 2025 Gavin Newsom on the L.A. Protests, Trump’s Response and Why it’s a Defining Moment for Democracy The New York Times, June 12 2025

Wren, A. 2025 Buttigieg gives the clearest sign yet about his next steps, POLITICO, March 13 2025

Books:

Tapper, J. 2025 Original Sin: President Biden's Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again, Penguin Press, 20 May 2025

Comments